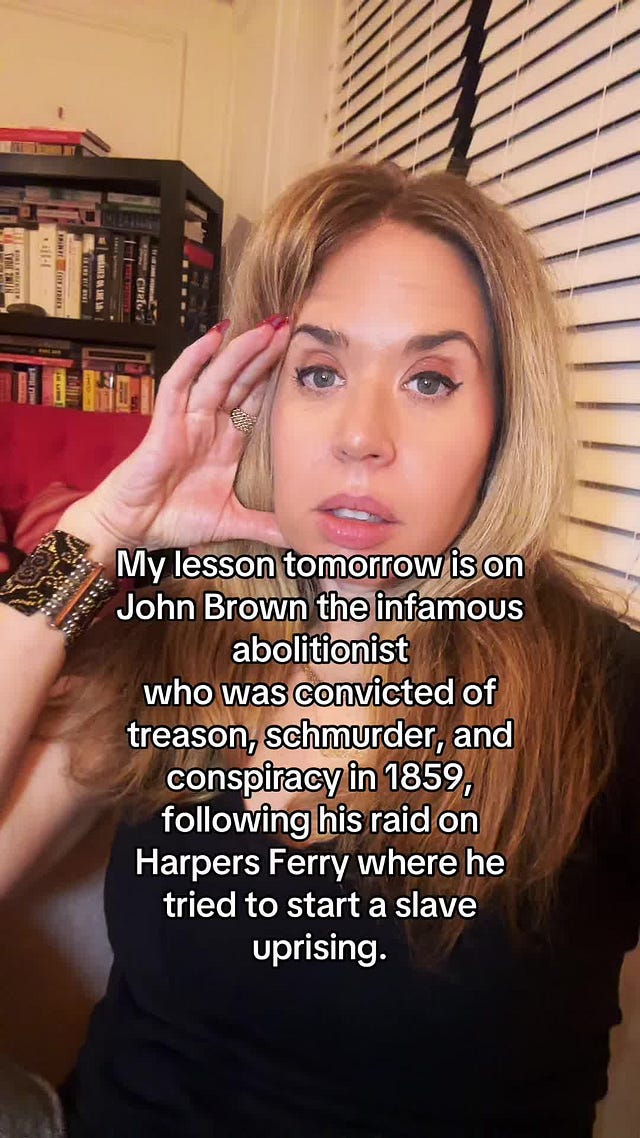

It is uncanny how the history I teach often aligns with today’s headlines. As I prepare tomorrow’s lesson on the historical vigilante John Brown, I find myself immersed in news coverage of Luigi Mangione, the alleged vigilante assassin of the United Healthcare CEO, Brian Thompson. Both figures resorted to violence to confront what they perceived as systemic injustices, raising timeless moral questions about justice and resistance.

Before proceeding, it’s crucial to emphasize that I am not equating the heinous practice of race-based chattel slavery with the deeply flawed health insurance system. The American slave system stands as one of the most horrific atrocities in human history. This comparison instead focuses on the broader question of whether violence can ever be justified in addressing systemic injustice. It also provides a thematic connection to current events, building on students’ reflections this week about the motives behind the alleged assassin’s actions.

After reading Mangione’s handwritten manifesto, it appears as though his actions were driven by a deep disdain for the health insurance industry and a desire to confront its exploitation of the American public. He accused these corporations of prioritizing profits over the well-being of Americans, describing them as "parasites" that have "simply gotten too powerful" and continue to exploit the country for immense profit. The internet’s reaction to Mangione is fascinating—some celebrate him as a folk hero challenging corporate greed, while others swoon over his appearance. Meanwhile, many across the political spectrum have praised his alleged attack on a corrupt system. The same polarized reaction happened with John Brown in his day: some revered him as a freedom fighter while others viewed him as a domestic terrorist.

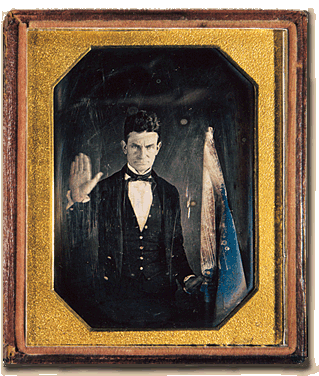

Meanwhile, as I delve into John Brown’s story, I’m struck by how another man, centuries earlier, also used violence to fight for a cause he believed in deeply: the abolition of race-based chattel slavery in the United States.

John Brown was a radical abolitionist who believed slavery was a moral atrocity that could only be eradicated through direct and violent action. His infamous raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, designed to incite a widespread slave rebellion, failed and led to his capture and execution. Brown saw himself as a martyr for justice, declaring in his final speech:

"I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done."

Brown’s actions reflect a far greater scale of violence than Mangione’s; sixteen people died during his raid on Harpers Ferry, including ten of his own men and two of those ten were his sons. Yet the underlying questions about the morality of violence are similar.

When, if ever, can violence be justified in the pursuit of justice?

The topic for our Socratic Seminar discussion tomorrow will be:

To what extent was John Brown a hero or a domestic terrorist?

I plan to start off the class with these main themes that I hope students will explore:

Moral vs. Legal: Were Brown’s actions justifiable given the moral atrocity of slavery?

Methods: Can violent methods be heroic if the cause is righteous?

Legacy: How did his actions influence the abolitionist movement and the Civil War?

Perspective: How might opinions of John Brown differ based on race, geography, or the time period?

The core discussion questions will be:

Was John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry a necessary act of resistance, or an irresponsible escalation?

Can violence ever be justified in the pursuit of justice?

How might contemporary labels like "terrorist" or "freedom fighter" shape our understanding of historical figures like John Brown?

How did John Brown’s actions contribute to the larger abolitionist cause and the lead-up to the Civil War?

I anticipate that this question "2. Can violence ever be justified in the pursuit of justice?” will lead to students bringing up other examples were violence was used to achieve justice in American history (and world history for that matter). I also expect many of the kids to think about Luigi Mangeone’s alleged actions.

To fully contextualize these discussions, it’s essential to recognize that America’s foundation was deeply rooted in violence. The Boston Massacre of 1770—a deadly clash between British soldiers and colonists—stands as a pivotal moment, galvanizing many colonists to join the revolutionary cause. The American Revolution itself was a violent struggle, justified by the Enlightenment ideals of liberty and self-determination, to overthrow colonial rule.

Fast forward to the era of John Brown, the Civil War became the most devastating conflict in American history, claiming over 600,000 lives. This violent war ultimately led to the abolition of slavery—just as John Brown predicted before his execution less than two years before its outbreak. In the aftermath of the war, during the Reconstruction Era, white supremacist violence targeted Black communities to suppress their newly gained citizenship and voting rights, perpetuating a legacy of racial oppression.

More recently, events like the January 6th insurrection—when Trump supporters violently attempted to stop the democratic process—underscore how violence continues to shape America. These moments remind us that violence has been both a destructive and transformative force throughout the nation’s history.

This is not me justifying violence. Rather, it’s a reflection on actual events in history as seen through the lens of a U.S. history teacher.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

The goal of my John Brown lesson is for students to engage in a nuanced discussion about his actions. Most years, students leave the lesson without a single answer. Instead, they often realize that assessments of John Brown’s actions depend on one’s perspective. The idea that “one person’s hero is another person’s terrorist” is always a strong takeaway.

At the end of the discussion, students complete a self-reflection assessment to solidify their thoughts. My hope is that this lesson will empower them to draw connections between recent headlines and the patterns of history, all while strengthening their critical thinking and historical analysis skills.

We will continue to return to these major themes throughout the school year:

How far should someone go to fight for justice?

How does perspective affect the way we view events in history as well as current day?

By helping students connect these historical and current day narratives, we not only deepen their understanding of the past but also empower them to engage thoughtfully with the complexities of the present—and the challenges of shaping the future.

Ultimately, this work is about fostering student agency and empowering their voices.

P.S. Here are some book recommendations if you want to read more about John Brown

Cloudsplitter by Russell Banks

The Good Lord Bird by James McBride (also an excellent TV series)

Fascinating connection. I hope your Socratic Seminars went well! And if they didn’t, remember the words of Walter Parker: “the most common feature of a successful Socratic Seminar is the teacher saying that it could have gone better”

John Brown's last statement proved prophetic as he said the "sins of slavery were to be washed away by blood"....and we had the Civil War.